Army Corps of Engineers, “National Economic Development: Flood Risk Management,” 2013.īut probability never works out perfectly in practice (as you know if you’ve ever flipped a coin twice and gotten heads or tails both times). A 2013 map of the estimated 100-year and 500-year floodplains for Harris County, where Houston is located.

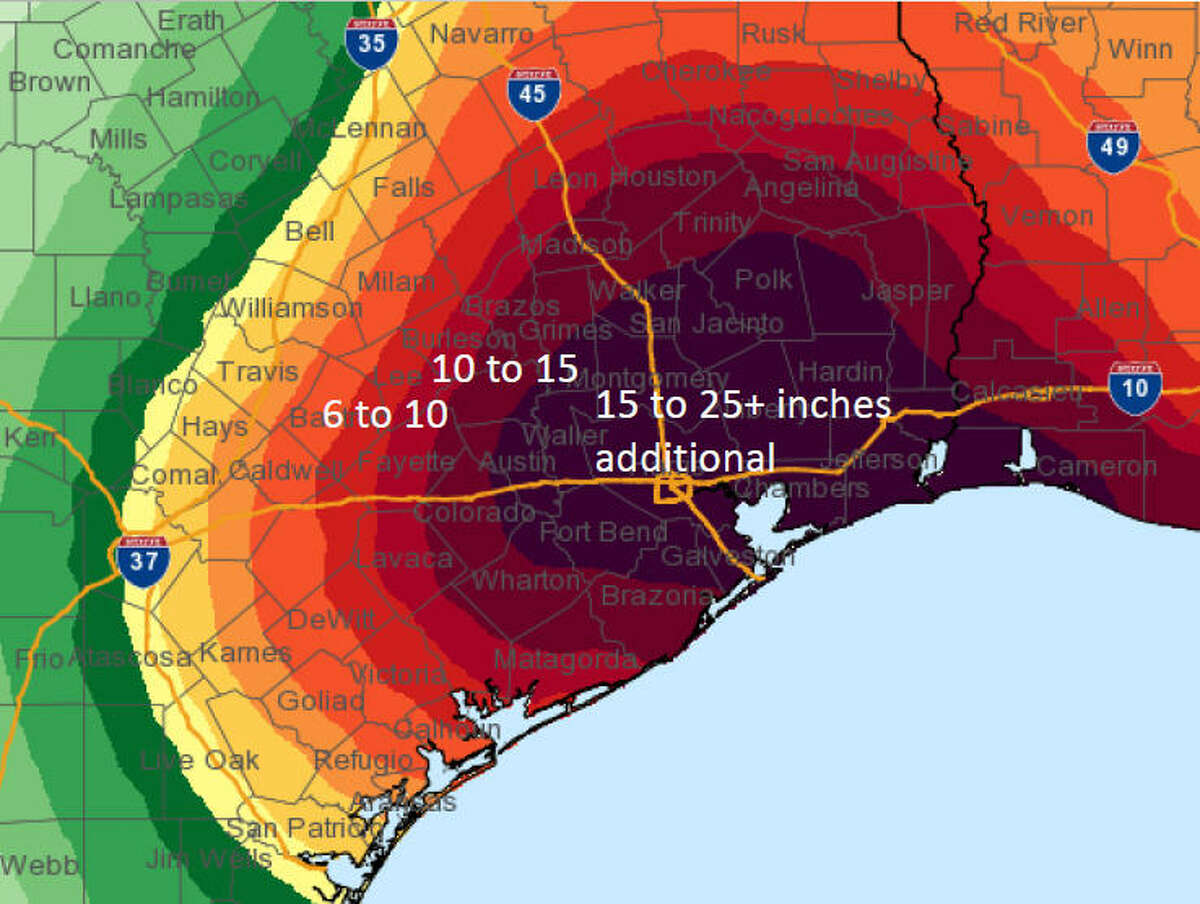

So FEMA maps out 100- and 500-year “floodplains” - the places that would get flooded by the kind of rainfall that has a 1 percent chance (or 0.2 percent chance) of falling on an area in any given year. When it comes to planning for future floods, you have to get a little more abstract. You can see that the flood reached 500-year levels in certain places, but in others it was the sort of event meteorologists would predict to happen every 10 years. This table, for example, shows the flooding in various locations in the Houston area in April 2016. So how bad a flood has to get to qualify as a 1-in-500-year flood is going to vary depending on where you’re judging it - and a flood will probably qualify as a “500-year” occurrence in some locations but not others. Of course, different areas flood at different frequencies. In theory, that means that over 500 years, that will happen once: so there will be one flood that bad over a 500-year period. The areas deemed at risk of a bad flood were the areas that had about a 1 percent chance of flooding in any given year: in other words, the areas that would flood approximately one year out of every 100.Ī 500-year flood is based on the same principle: Experts estimate that in any given year, there’s a 1-in-500 (0.2 percent) chance a flood this bad will strike a particular area. Instead, the standard set for mapping flood-prone areas was a compromise between the existing Army Corps of Engineers standards for dams and levees, and the (much more modest) standards that most communities had set for flood prevention. When the government decided to map flood-prone areas to improve the National Flood Insurance Program in the early 1970s, the maps couldn’t just use the worst flood ever recorded in a given area to judge what a “bad flood” would look like - because some areas had more records than others, and besides, just because a bad flood hadn’t happened yet didn’t mean it couldn’t. The lack of hundreds of years’ worth of flood data is actually the reason we have the term “100-year” flood to begin with. But this isn’t an assessment of “the worst flood in” that time - places like Houston don’t actually have detailed weather records going back to 1017 AD, after all. The severity of floods tends to get put in terms of years: a 100-year flood, a 500-year flood, a 1,000-year flood. “500-year” floods are based not on history, but on probability And, especially in Houston, prevention planning hasn’t evolved to acknowledge that a “500-year” flood isn’t really a 1-in-500 chance anymore.

The problem is that 500-year floods are happening more often than probability predicts - especially in Houston. In theory, a 500-year flood is something that has a 1-in-500 shot of happening in any given year - in other words, the sort of event that’s so rare that it might not make sense to plan around the possibility of it happening. In the final reckoning, it’s certain that Harvey will be classified a 500-year flood - and maybe even a 1,000-year flood.īut those terms can be a bit misleading - especially when high-profile people, like the president of the United States, confuse the issue by calling Harvey “a once in 500 year flood.” Weather experts call the storm unprecedented, and note that it’s gone beyond even the most pessimistic forecasts. It’s difficult to comprehend the scale of the flooding and devastation that Hurricane Harvey and its aftermath are wreaking on the Houston area.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)